Old Broad Street, what a beautiful picture! Shame

that we could not preserve and blend our old ways

to suit our modern lives. We still have the types of

the black caps in the picture up till today in UK

manufactured in their likes and as new as 2012

models. Alas, things have gone from bad to worse

and from worse to worst in Nigeria. The only

things we renew seems to be corruption, looting

and stealing as well as other vices both in high

and low places. I weep for my country.

I do not know if your generation met the majestic

St. Anna court building which was razed to the

ground. I’m still on the look-out for any old

picture. At Ibadan, just about all the old colonial

buildings in the different Government Residential

Areas (GRAs) AND at Lagos, especially Ikoyi, have

been sold off government hands. The buyers (top

government and industry types), especially at Ikoyi

– in pursuit of humongous profits – have razed

the grand old buildings down and replaced them

with soul-less modern boxes, mostly multi-family

dwellings. The case of Ikoyi is a big disgrace

because those properties could have been sold

with a condition that the exterior be not subjected

to architectural/structural modifications.

Places such as properties around Queen Street,

Yaba (Lagos) will soon disappear, and gone would

be the old Brazilian-type architectural small

bungalows. On my rare visits to Lagos, I never fail

to hope the Okupes would not allow Agbonmagbe

House, the building that housed the old

Agbonmagbe Bank, Nigeria’s first indigenous bank

founded by late Chief Okupe, to go the way of

many that are being sold for huge amounts.

After Adekunle Police Station on Herbert Macaulay

and just before the turn-off (left) towards the Third

Mainland Bridge, the quaint Brazilian-design

bungalow is on the right.

I’m aware that the house still remains in family

hands but how long this will stand in the face of

tons of money that such a place can attract is

anybody’s guess unless, of course, Lagos State

Government can start paying attention to the area

of acquisitions of a few places to serve as small

museums, etcetera to hold Yoruba artefacts.

Philanthropists are also needed to rise to the

challenge of donating places that would ensure

generations yet unborn would not meet huge

buildings with no pasts in the future.

I never stop wondering how our ancestors: the

Edos of Benin Kingdom, the Middle Belters, the

Yoruba, Sokoto, etcetera – all in Nigeria – came

up with those magnificent Opa Oranyan & Ori

Olokun (Ile-Ife), etcetera; Benin Bronze heads; the

magnificent Nok Culture terracottas centuries, in

some cases, over 1000 years ago AND YET, we the

descendants, continue to feel no shame about our

lack of any additions to these wondrous works.

Your note, Dear Fatai, has gotten me thinking of

something I’ve planned to showcase for a while

that may lead us to a path that I believe we

Africans must pursue. Ten years ago this month, I

wondered aloud about the original manuscript for

Rev. Johnson’s “The History of the Yorubas” in my

weekly essays for a newspaper as “The manuscript

that got lost: Remembering the Rev. Samuel

Johnson (Ayinla Ogun).

All the wondrous works below from different parts

of Nigeria – with the exception of the monolith at

Ile-Ife (Opa Oranyan) lie in various museums and

private collections of the Western world: the

British Museum, The Louvre in Paris, and many

university collections in the West.

Now, I’m not talking of getting these irreplaceable

works of arts back but shouldn’t their creation be

enough to spur Nigerians to strife for excellence?

Shouldn’t the creation of magnificent works of arts

by our African ancestors West, East and South of

the Continent – the North are much different – be

enough impetus for us to raise our heads by

striving for excellence rather than the corruption

that envelope us?

While waiting for a renaissance of spirit in us all,

let’s feast our eyes on a tiny few of these

incredible works that were stolen, taken for a song

many times over or given as gifts through trickery

by Westerners who came to “civilize” our

ancestors. Remember my reference to how Alake

of Egbaland Late Oba Lipede refused to part with

ANOTHER ancient Bible that a white guy

purportedly wanted to take to England to “re-bind/

repair”. The monarch said, ‘no thanks’

remembering the palace lost a previous one

through the same kind of “assistance”.

The Nok Culture of the Middle Belt appeared from

around 500 BC to 200 AD – about thousand years

ago but somehow disappeared! If the civilizations

that produced those wondrous works somehow

disappeared, what happened and what have we

done about them?

Below are some pictures from the web; many of

us have seen the most popular ones while many

may be new. The publication of the old Broad

Street picture even though it does not contain

much AND Fatai Bakare’s comments got me going

on this.

It’s all v. depressing but also v. exhilarating as

regards our heritage. It’s about the same all over

Africa..

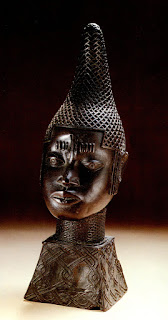

Nigeria; Benin Kingdom peoples

Head

Clay

H. 21 cm (8 ¼”)

National Museum, Lagos, Nigeria, 60.3.2

Benin art became well-known to the West in

1897, after the British Punitive Expedition

sacked the city of Benin and brought

thousands of objects back to Europe as war

booty. The origins of the kingdom probably go

back more than 500 years. According to oral

history the people of Benin were first ruled by

the Ogiso kings, but the people revolted and

asked the King of Ife to send a prince to rule

them. He sent Oranmiyan, whose first son

Eweka became the first Oba or king of the new

dynasty. Terracotta heads, such as this one

dated to the late 15th or 16th century, were

used by the Ogiso rulers on altars to their

paternal ancestors (Girshik Ben-Amos 1995:

22). Other clay heads were used more recently

by the royal guild of brass casters on an altar

to Igueghae, who some as NJsert introduced brass

casting from Ife (Eyo and Willett 1980:130).

Nigeria; Benin Kingdom peoples

Leopards

Bronze

L. 69 cm (27 3/16”)

National Museum, Lagos, Nigeria, 52.13.1,

52.13.2

Photo by Dirk Bakker

This pair of leopards, probably from the

sixteenth-century, are actually water vessels

(aquamanile), which are used for making ritual

ablutions by pouring the water out through the

nostrils. Such cast leopards were kept on the

royal ancestral altars and were used by the

Oba, when he prepared himself for the Ugie

Erha Oba ceremony, in which he honors his

deceased father. Leopards appear frequently in

Benin art, and there was a special guild of

leopard hunters who captured leopards. Some

were sacrificed, others were tamed, and the

Oba led them in processions as symbols of his

control over his counterpart, the king of the

forests (Girshick Ben-Amos 1995: 15). A

seventeenth-century engraving, based on a

Dutch visitor’s observations of Benin, shows

the Oba in procession with his tame leopards

Nigeria; Edo peoples ( Benin Kingdom Court

Style)

Commemorative trophy head

Late 15th-early 16th century

Copper alloy, iron inlay

H x W x D: 23.2 x 15.9 x 20 cm (9 1/8 x 6 1/4

x 7 7/8 in.)

Purchased with funds provided by the

Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program

82-5-2

Photograph by Franko Khoury

National Museum of African Art

Smithsonian Institution

Benin history is focused primarily on the thirty-

eight Obas (“kings”), who have ruled since the

founding of the dynasty. At the death of an

Oba, one of his successor's first

responsibilities is to establish an altar to his

memory. Commoners and chiefs also do this

for their predecessors with rectangular altars

and wooden commemorative heads. Only the

royalty are allowed to have semicircular altars,

and the use of brass to cast commemorative

heads is an exclusive royal prerogative. William

Fagg argued that this type of brass head with a

short, tight collar represented the very earliest

type of memorial head after brass casting was

introduced from Ife. Paula Girshick Ben-Amos,

however, feels they are not kings at all because

they do not wear crowns. She claims they are

trophy heads of decapitated enemy rulers

(Girshick Ben-Amos 1995: 26).

Nigeria; Edo peoples ( Benin Kingdom Court

Style)

Commemorative head of a king

19th century

Copper alloy

H x W x D: 38.1 x 24.4 x 27 cm (15 x 9 5/8 x

10 5/8 in.)

Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn to the Smithsonian

Institution in 1966

85-19-7

Photograph by Franko Khoury

National Museum of African Art

Smithsonian Institution

The high-collared heads seen in the previous

example are from the Middle Period, the same

period when plaques were introduced, the early

sixteenth to the late seventeenth century. The

Late Period, when this head was made, dates

from the late seventeenth century to 1897,

when the city was sacked by the British. During

this period the king was sent into exile, and

brass casting ceased for a while until a new

king, Eweka II, was installed in 1914. Each Oba

added embellishments to the beaded coral

crown as the dynasty continued, and the

commemorative heads reflect this cumulative

nature. As time went on, more brass became

available through trade, and commemorative

heads became heavier. Before 1897 we think

there were altars for each deceased king. Now

there is one altar for the kings who ruled after

the sack of Benin and one for those who ruled

before 1897 (Plankensteiner 2007).

Nigeria; Benin Kingdom peoples

Queen Mother head

Bronze

H. 53.3 cm (21")

Detroit Institute of Arts, City of Detroit

Purchase, 26.180

The Queen Mothers’ heads went through the

same series of stylistic transformation as the

kings’ heads. This much heavier casting, with

the high beaded collar, dates from the Late

Period of casting, probably the nineteenth

century. The Queen Mothers were also allowed

to have carved tusks on their altars. While the

animal symbol most commonly associated with

the king was the leopard, the symbol of the

Queen Mother was the hen, and carved images

of hens were also placed on her altars. Apart

from the Oba and his intricate coral bead outfit,

only “the Queen Mothers, the Crown Prince and

the Ezomo [high ranking chiefs and military

commanders] are permitted to wear a beaded

shirt and crown” (Girshick Ben-Amos 1995:

89).

Nigeria; Benin Kingdom peoples

Equestrian figure

Bronze

H. 47 cm (18 1/2")

Detroit Institute of Arts, Gift of Mrs. Walter B.

Ford II, 1992.290

From an 1823 account of the explorer Giovanni

Belzoni and an accompanying sketch, we have

one of the few descriptions and drawings of

altars of the Kings of Benin before 1897, when

all were dismantled. Equestrian figures such as

this were apparently included on the altars, but

who is represented is the matter of

considerable debate. Some have suggested the

figure is an emissary from the north, others

that it represents an enemy, the King of Idah.

Paula Girshik Ben-Amos suggests the

“horseman may represent Oranmiyan, the

founder of the second dynasty, who is said to

have introduced horses into Benin, and who is

also associated with the foundation of the

Yoruba kingdom of Oyo, which rose to power

through its mounted armies. The fact that such

figures were placed on ancestral altars seems

to support this identification” (1995: 54).

Nigeria; Benin Kingdom peoples

Figure

Bronze

H. 63.5 cm (25”)

National Museum, Lagos, Nigeria, 54.15.8

Photo by Dirk Bakker

This type of figure was apparently also kept on

the royal ancestral altars. An anonymous author

in the Royal Gold Coast Gazette wrote in the

1820s, “The tombs are decorated by as many

large elephant’s teeth as can be set in the

space; and the socket of the tooth is

introduced into the crown of the head of a

colossal brazen bust, ... The other figures on

these monuments are very happy, a blacksmith

on an ass, and a carpenter in the act of striking

with an axe, are well portrayed” (cited in

Girshik Ben-Amos 1995: 53). The “axe” is

actually a blacksmith’s hammer. Eyo and Willett

describe the figure as the messenger who

carried the emblems of authority—a bronze

cap, a stall, and a cross—from Ife to Benin

(1980: 133). Others suggest it represents one

of the Benin court officials who wear the cross

as their emblem.

There are over 900 plaques dating from the

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This was

the period of great warrior kings. Benin

conquered surrounding areas and expanded the

kingdom as far west as Wydah (in modern

Benin) and as far east as the Niger River. The

sixteenth century was also the period when the

Portuguese arrived bringing trade goods

(especially a steady supply of brass) and

providing mercenary troops. This was also a

time of great artistic production, and a number

of art forms, such as the plaques, began and

flourished during this era. Because a two-

dimensional rectangular format is unusual for

African art, scholars assume that the artists

who made the plaque had seen European

books. The subject matter is primarily of

political ritual, this one for example, shows

some of the court attendants.

Nigeria; Edo peoples ( Benin Kingdom Court

Style)

Plaque

Mid 16th-17th century

Copper alloy

H x W x D: 47 x 34.2 x 8.2 cm (18 1/2 x 13

7/16 x 3 1/4 in.)

Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn to the Smithsonian

Institution in 1979

85-19-18

Photograph by Franko Khoury

National Museum of African Art

Smithsonian Institution

Figures appear in hierarchical perspective:

those who are more important are depicted

larger. The servant who holds the sword is

smaller than the king or war chief who

dominates the center of the plaque. Several

Portuguese appear with their stylized hats and

hair, but it is not certain whether they are

meant to be real men or a symbol of Olokun,

the god of the waters and wealth. Girshik Ben-

Amos interprets the background quatrefoil

design of many of the plaques as a symbol of

Olokun (1995: 40). All the plaques show nail

holes, evidence that they were once attached to

pillars or walls of the palace. By 1700 they

were no longer being used and had been

removed, and in 1897 they were all found

stacked up in storage.

that we could not preserve and blend our old ways

to suit our modern lives. We still have the types of

the black caps in the picture up till today in UK

manufactured in their likes and as new as 2012

models. Alas, things have gone from bad to worse

and from worse to worst in Nigeria. The only

things we renew seems to be corruption, looting

and stealing as well as other vices both in high

and low places. I weep for my country.

I do not know if your generation met the majestic

St. Anna court building which was razed to the

ground. I’m still on the look-out for any old

picture. At Ibadan, just about all the old colonial

buildings in the different Government Residential

Areas (GRAs) AND at Lagos, especially Ikoyi, have

been sold off government hands. The buyers (top

government and industry types), especially at Ikoyi

– in pursuit of humongous profits – have razed

the grand old buildings down and replaced them

with soul-less modern boxes, mostly multi-family

dwellings. The case of Ikoyi is a big disgrace

because those properties could have been sold

with a condition that the exterior be not subjected

to architectural/structural modifications.

Places such as properties around Queen Street,

Yaba (Lagos) will soon disappear, and gone would

be the old Brazilian-type architectural small

bungalows. On my rare visits to Lagos, I never fail

to hope the Okupes would not allow Agbonmagbe

House, the building that housed the old

Agbonmagbe Bank, Nigeria’s first indigenous bank

founded by late Chief Okupe, to go the way of

many that are being sold for huge amounts.

After Adekunle Police Station on Herbert Macaulay

and just before the turn-off (left) towards the Third

Mainland Bridge, the quaint Brazilian-design

bungalow is on the right.

I’m aware that the house still remains in family

hands but how long this will stand in the face of

tons of money that such a place can attract is

anybody’s guess unless, of course, Lagos State

Government can start paying attention to the area

of acquisitions of a few places to serve as small

museums, etcetera to hold Yoruba artefacts.

Philanthropists are also needed to rise to the

challenge of donating places that would ensure

generations yet unborn would not meet huge

buildings with no pasts in the future.

I never stop wondering how our ancestors: the

Edos of Benin Kingdom, the Middle Belters, the

Yoruba, Sokoto, etcetera – all in Nigeria – came

up with those magnificent Opa Oranyan & Ori

Olokun (Ile-Ife), etcetera; Benin Bronze heads; the

magnificent Nok Culture terracottas centuries, in

some cases, over 1000 years ago AND YET, we the

descendants, continue to feel no shame about our

lack of any additions to these wondrous works.

Your note, Dear Fatai, has gotten me thinking of

something I’ve planned to showcase for a while

that may lead us to a path that I believe we

Africans must pursue. Ten years ago this month, I

wondered aloud about the original manuscript for

Rev. Johnson’s “The History of the Yorubas” in my

weekly essays for a newspaper as “The manuscript

that got lost: Remembering the Rev. Samuel

Johnson (Ayinla Ogun).

All the wondrous works below from different parts

of Nigeria – with the exception of the monolith at

Ile-Ife (Opa Oranyan) lie in various museums and

private collections of the Western world: the

British Museum, The Louvre in Paris, and many

university collections in the West.

Now, I’m not talking of getting these irreplaceable

works of arts back but shouldn’t their creation be

enough to spur Nigerians to strife for excellence?

Shouldn’t the creation of magnificent works of arts

by our African ancestors West, East and South of

the Continent – the North are much different – be

enough impetus for us to raise our heads by

striving for excellence rather than the corruption

that envelope us?

While waiting for a renaissance of spirit in us all,

let’s feast our eyes on a tiny few of these

incredible works that were stolen, taken for a song

many times over or given as gifts through trickery

by Westerners who came to “civilize” our

ancestors. Remember my reference to how Alake

of Egbaland Late Oba Lipede refused to part with

ANOTHER ancient Bible that a white guy

purportedly wanted to take to England to “re-bind/

repair”. The monarch said, ‘no thanks’

remembering the palace lost a previous one

through the same kind of “assistance”.

The Nok Culture of the Middle Belt appeared from

around 500 BC to 200 AD – about thousand years

ago but somehow disappeared! If the civilizations

that produced those wondrous works somehow

disappeared, what happened and what have we

done about them?

Below are some pictures from the web; many of

us have seen the most popular ones while many

may be new. The publication of the old Broad

Street picture even though it does not contain

much AND Fatai Bakare’s comments got me going

on this.

It’s all v. depressing but also v. exhilarating as

regards our heritage. It’s about the same all over

Africa..

Head

Clay

H. 21 cm (8 ¼”)

National Museum, Lagos, Nigeria, 60.3.2

Benin art became well-known to the West in

1897, after the British Punitive Expedition

sacked the city of Benin and brought

thousands of objects back to Europe as war

booty. The origins of the kingdom probably go

back more than 500 years. According to oral

history the people of Benin were first ruled by

the Ogiso kings, but the people revolted and

asked the King of Ife to send a prince to rule

them. He sent Oranmiyan, whose first son

Eweka became the first Oba or king of the new

dynasty. Terracotta heads, such as this one

dated to the late 15th or 16th century, were

used by the Ogiso rulers on altars to their

paternal ancestors (Girshik Ben-Amos 1995:

22). Other clay heads were used more recently

by the royal guild of brass casters on an altar

to Igueghae, who some as NJsert introduced brass

casting from Ife (Eyo and Willett 1980:130).

Nigeria; Benin Kingdom peoples

Leopards

Bronze

L. 69 cm (27 3/16”)

National Museum, Lagos, Nigeria, 52.13.1,

52.13.2

Photo by Dirk Bakker

This pair of leopards, probably from the

sixteenth-century, are actually water vessels

(aquamanile), which are used for making ritual

ablutions by pouring the water out through the

nostrils. Such cast leopards were kept on the

royal ancestral altars and were used by the

Oba, when he prepared himself for the Ugie

Erha Oba ceremony, in which he honors his

deceased father. Leopards appear frequently in

Benin art, and there was a special guild of

leopard hunters who captured leopards. Some

were sacrificed, others were tamed, and the

Oba led them in processions as symbols of his

control over his counterpart, the king of the

forests (Girshick Ben-Amos 1995: 15). A

seventeenth-century engraving, based on a

Dutch visitor’s observations of Benin, shows

the Oba in procession with his tame leopards

Style)

Commemorative trophy head

Late 15th-early 16th century

Copper alloy, iron inlay

H x W x D: 23.2 x 15.9 x 20 cm (9 1/8 x 6 1/4

x 7 7/8 in.)

Purchased with funds provided by the

Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program

82-5-2

Photograph by Franko Khoury

National Museum of African Art

Smithsonian Institution

Benin history is focused primarily on the thirty-

eight Obas (“kings”), who have ruled since the

founding of the dynasty. At the death of an

Oba, one of his successor's first

responsibilities is to establish an altar to his

memory. Commoners and chiefs also do this

for their predecessors with rectangular altars

and wooden commemorative heads. Only the

royalty are allowed to have semicircular altars,

and the use of brass to cast commemorative

heads is an exclusive royal prerogative. William

Fagg argued that this type of brass head with a

short, tight collar represented the very earliest

type of memorial head after brass casting was

introduced from Ife. Paula Girshick Ben-Amos,

however, feels they are not kings at all because

they do not wear crowns. She claims they are

trophy heads of decapitated enemy rulers

(Girshick Ben-Amos 1995: 26).

Style)

Commemorative head of a king

19th century

Copper alloy

H x W x D: 38.1 x 24.4 x 27 cm (15 x 9 5/8 x

10 5/8 in.)

Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn to the Smithsonian

Institution in 1966

85-19-7

Photograph by Franko Khoury

National Museum of African Art

Smithsonian Institution

The high-collared heads seen in the previous

example are from the Middle Period, the same

period when plaques were introduced, the early

sixteenth to the late seventeenth century. The

Late Period, when this head was made, dates

from the late seventeenth century to 1897,

when the city was sacked by the British. During

this period the king was sent into exile, and

brass casting ceased for a while until a new

king, Eweka II, was installed in 1914. Each Oba

added embellishments to the beaded coral

crown as the dynasty continued, and the

commemorative heads reflect this cumulative

nature. As time went on, more brass became

available through trade, and commemorative

heads became heavier. Before 1897 we think

there were altars for each deceased king. Now

there is one altar for the kings who ruled after

the sack of Benin and one for those who ruled

before 1897 (Plankensteiner 2007).

Nigeria; Benin Kingdom peoples

Queen Mother head

Bronze

H. 51 cm (20”)

National Museum, Lagos, Nigeria, 70.R.17

Photo by Dirk Bakker

Oba Esigie, the sixteenth king who ruled at the

beginning of the sixteenth century, created the

title of Queen Mother. His mother, Idia, was

said to have had particularly potent occult

skills and military savvy that helped Esigie

defeat the Igala people. He created the title to

honor her and is said to have established the

tradition of casting this type of brass head. It

shows the Queen Mother with her distinctive

hair style called the “chicken’s beak.” Since the

time of Esigie each Oba has conferred this title

on his mother three years after his accession

to the throne. These cast heads were placed

both on the altars in the palace and at the

Queen Mother’s residence (Girshick Ben-Amos

1995: 36).

Queen Mother head

Bronze

H. 53.3 cm (21")

Detroit Institute of Arts, City of Detroit

Purchase, 26.180

The Queen Mothers’ heads went through the

same series of stylistic transformation as the

kings’ heads. This much heavier casting, with

the high beaded collar, dates from the Late

Period of casting, probably the nineteenth

century. The Queen Mothers were also allowed

to have carved tusks on their altars. While the

animal symbol most commonly associated with

the king was the leopard, the symbol of the

Queen Mother was the hen, and carved images

of hens were also placed on her altars. Apart

from the Oba and his intricate coral bead outfit,

only “the Queen Mothers, the Crown Prince and

the Ezomo [high ranking chiefs and military

commanders] are permitted to wear a beaded

shirt and crown” (Girshick Ben-Amos 1995:

89).

Nigeria; Benin Kingdom peoples

Equestrian figure

Bronze

H. 47 cm (18 1/2")

Detroit Institute of Arts, Gift of Mrs. Walter B.

Ford II, 1992.290

From an 1823 account of the explorer Giovanni

Belzoni and an accompanying sketch, we have

one of the few descriptions and drawings of

altars of the Kings of Benin before 1897, when

all were dismantled. Equestrian figures such as

this were apparently included on the altars, but

who is represented is the matter of

considerable debate. Some have suggested the

figure is an emissary from the north, others

that it represents an enemy, the King of Idah.

Paula Girshik Ben-Amos suggests the

“horseman may represent Oranmiyan, the

founder of the second dynasty, who is said to

have introduced horses into Benin, and who is

also associated with the foundation of the

Yoruba kingdom of Oyo, which rose to power

through its mounted armies. The fact that such

figures were placed on ancestral altars seems

to support this identification” (1995: 54).

Figure

Bronze

H. 63.5 cm (25”)

National Museum, Lagos, Nigeria, 54.15.8

Photo by Dirk Bakker

This type of figure was apparently also kept on

the royal ancestral altars. An anonymous author

in the Royal Gold Coast Gazette wrote in the

1820s, “The tombs are decorated by as many

large elephant’s teeth as can be set in the

space; and the socket of the tooth is

introduced into the crown of the head of a

colossal brazen bust, ... The other figures on

these monuments are very happy, a blacksmith

on an ass, and a carpenter in the act of striking

with an axe, are well portrayed” (cited in

Girshik Ben-Amos 1995: 53). The “axe” is

actually a blacksmith’s hammer. Eyo and Willett

describe the figure as the messenger who

carried the emblems of authority—a bronze

cap, a stall, and a cross—from Ife to Benin

(1980: 133). Others suggest it represents one

of the Benin court officials who wear the cross

as their emblem.

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This was

the period of great warrior kings. Benin

conquered surrounding areas and expanded the

kingdom as far west as Wydah (in modern

Benin) and as far east as the Niger River. The

sixteenth century was also the period when the

Portuguese arrived bringing trade goods

(especially a steady supply of brass) and

providing mercenary troops. This was also a

time of great artistic production, and a number

of art forms, such as the plaques, began and

flourished during this era. Because a two-

dimensional rectangular format is unusual for

African art, scholars assume that the artists

who made the plaque had seen European

books. The subject matter is primarily of

political ritual, this one for example, shows

some of the court attendants.

Style)

Plaque

Mid 16th-17th century

Copper alloy

H x W x D: 47 x 34.2 x 8.2 cm (18 1/2 x 13

7/16 x 3 1/4 in.)

Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn to the Smithsonian

Institution in 1979

85-19-18

Photograph by Franko Khoury

National Museum of African Art

Smithsonian Institution

Figures appear in hierarchical perspective:

those who are more important are depicted

larger. The servant who holds the sword is

smaller than the king or war chief who

dominates the center of the plaque. Several

Portuguese appear with their stylized hats and

hair, but it is not certain whether they are

meant to be real men or a symbol of Olokun,

the god of the waters and wealth. Girshik Ben-

Amos interprets the background quatrefoil

design of many of the plaques as a symbol of

Olokun (1995: 40). All the plaques show nail

holes, evidence that they were once attached to

pillars or walls of the palace. By 1700 they

were no longer being used and had been

removed, and in 1897 they were all found

stacked up in storage.

Nigeria; Benin Kingdom peoples

Plaque

Bronze

H. 43 cm (16 15/16”)

National Museum, Lagos, Nigeria, 48.36.40

Photo by Dirk Bakker

This plaque shows isiokuo (a war ritual) in

honor of the god of war and iron, Ogun. An

acrobatic amufi (dance) is represented,

recalling a legendary war against the sky (Eyo

and Willett 1980: 137). In the top of the tree

are three ibises or “birds of disaster.” The

birds refer to a story about one of the great

warrior kings, Esigie. As he was going to war

against his enemy, the Igala, the ibis cried out

that disaster lay ahead. Instead of heeding the

warning, Esigie had the bird killed and

“proclaimed that ‘whoever wishes to succeed in

life should not heed the bird of

prophecy’” (Girshick Ben-Amos 1995: 35).

Esigie had the brass casters make a staff in the

image of the bird to commemorate the event,

and these staffs continue to be used in the

festival Ugie Oro, honoring each king’s dead

father.

Nigeria; Benin Kingdom peoples

Head of an Oba

Bronze

H. 29.2 cm (11 1/2")

Indiana University Art Museum, 75.98

Other types, however, are indisputably

commemorative heads to be placed on the

altars of former kings. Carved ivory tusks are

placed in the top, for ivory was another

material reserved for royalty, and there are

special guilds of artists who only carve ivory

for the king. Brass has special meaning in

Benin. Because it never rusts or corrodes it

represents the permanence and continuity of

the institution of kingship. It is considered

beautiful, and in the past the royal brasses (of

which there are a wide variety: from pendants,

plaques, staffs, and stools to masks and

commemorative heads) were polished to bring

out their shine. Brass “is red in color and this

is considered by the Edo [people of Benin] to

be ‘threatening,’ that is, to have the power to

drive away evil forces” (Girshick Ben-Amos

1995: 88). TO BE CONTINUED.....

Comments

Post a Comment